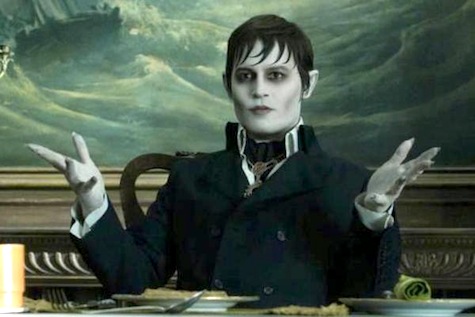

What with the popularity of vampires on television, Dark Shadows and The Raven in movie theaters, and a new paranormal romance paperback coming out every day, you might think that Gothic was more popular than ever.

But is it really? What is Gothic, anyway? It’s one of those terms that you think you know until you have to define it. Is True Blood part of the Gothic tradition?

Though it’s sometimes looked down on as a mixture of horror and romance, Gothic literature has been and continues to be a tremendously influential and popular genre. For instance, think of Dracula and the enormous influence that book has had on culture. How many single books can claim to have had the same impact on the minds of so many people—many of whom have never read it?

If horror isn’t a genre but a feeling (as horror writers assert), Gothic includes the element of horror but has other earmarks that would qualify it as a sub-genre, at the least. And, as I’m about to argue, a lot of the novels written today with the trappings of Gothic—vampires or werewolves, castles, dark and stormy nights and an abundance of black bunting decorating the stairwells—are not part of the Gothic tradition.

What makes a book Gothic? Generally speaking, at its core Gothic fiction has these characteristics: (1) the main character is being asked to reject the rational world in order to embrace the primitive world of our emotions; (2) this is usually done through a supernatural element that invokes a feeling of dread or terror; (3) the supernatural world is represented by a character who has completely rejected the rational world for this primitive world; and (4) the story serves to warn the reader of the danger of giving oneself over to the seductive but dangerous world of the inner psyche.

In most Gothic stories, the main character starts out as part of the adult world of logic and reason, but gradually surrenders to a growing sense of dread that something is not right. The terror she feels is from the supernatural—the supernatural world representing the world of emotion and feeling, the world from which we become estranged when we become part of the rational world.

Another characteristic of Gothic literature is the presence of a character that is already in touch with this primitive side, the one who is part of the supernatural world. This character, usually male, represents the “sublime power of the irresistible force” of the primitive, to quote Valdine Clemens in The Return of the Repressed, a great analysis of Gothic literature. Today’s fiction teems with these characters: easily forty percent of today’s bad boys of fiction are vampires, werewolves, fallen angels or even zombies. Clearly, they’re paranormal—but does that make them Gothic?

It’s the fourth characteristic of Gothic literature—that it serves as a cautionary tale—that divides Gothic from much of the paranormal and horror novels written today. Because if there’s one theme that runs through most of these books, it’s not that we fear or dread the supernatural creature, but that we want to BE the supernatural creature. There’s sometimes a token resistance to the supernatural creature akin to the argument that goes on in a virgin’s head before the moment of surrender: charming but completely disingenuous. The tension in these stories comes from something else—searching for a holy relic, pursuing a supernatural criminal or trying to save your friends from annihilation—but not from a mortal fear that your soul or your sanity is going to be swallowed up by the dark incubus lying in wait.

So, using these criteria, which books (or movies and television shows) written in the past few decades would you say follows the Gothic tradition? Obviously, everything written by Anne Rice. John Harwood (The Ghostwriter, The Séance), Sarah Waters’ The Little Stranger, Kate Morton’s The Distant Hours. Or would you argue that the definition of Gothic should be expanded?

Alma Katsu is the author of The Taker (Gallery Books/Simon & Schuster), a Gothic novel about obsessive love and a very dangerous man of the supernatural persuasion. The Taker was selected by Booklist as one of the top ten debut novels of 2011. The Reckoning, the second book in the trilogy, is out on June 19.

Thank Alma, that makes it much clearer.

deb

As it says on my T-shirt*: Where were you when we sacked Rome?

* True Story: I was wearing this shirt at Denvention when I met Steve Jackson for the first time.

Gothics are hard to define, but I’ll take a stab at how I see it. To me they are about atmosphere. There doesn’t have to be any supernatural element, just the hint of evil and dread. In older gothic romance it’s often created by implying the hero murdered his wife.

Gothics also include isolation of the heroine or hero or group, so they’re completely on their own. And, in book form, the story is told from their point of view so we can experience their dread and lack of knowledge first hand.

The source of tension to me does always have an external element, but good gothics are always about the fight within the heroine (or hero). She’s drawn to things she’s not supposed to want, she’s scared of them and what’s happening around her, she has no idea who to trust, sometimes up until the last page when she figures it out. It’s all about the conflict inside her. I love the point where she steps out of that child-like shell and becomes an adult and makes her decisions.

Mary Stewart’s Nine Coaches Waiting is a classic gothic suspense novel that I think is the epitome of all that’s good about the genre. True Blood is Southern Gothic, a subgenre of its own (there’s also what I call a New England gothic, generally about witches or small towns with covens that sacrifice people).

I’ve not read many gothics that have been written in the last 30 years or so, but I see what look like gothics among YA selections a lot. I think the alienation a teenager naturally feels is a perfect pairing with the genre.

Alma, I need to brush up on my history of Gothic texts, but I know we can go back further than Dracula for a novel that’s probably just as huge in terms of influence and lasting fame: Frankenstein. It incorporates every element you listed.

Should the definition of Gothic be expanded? I don’t know. I feel like the supernatural and paranormal works could overwhelm the earlier definition, until the Gothic tradition is just credited as the founder of those genres. Then again, maybe there will be a resurgence in Gothic fiction.

By the way, thanks for breaking down the four elements of gothic works. That’s as succint a breakdown as anyone could wish for.

Shelly and Errant, Good points! Gothic seems to be one of those things that is in the eye of the beholder. I wasn’t a Mary Stewart reader back in the day, but I feel as though I should fix that gap. Errant, many lit theory types point to The Castle of Otranto as the first Gothic novel, written in 1764 by Horace Walpole. Melmoth the Wanderer by Charles Robert Maturin, written in 1820, is the earliest Gothic novel I’ve read personally.

I’d argue that the supernatural is not strictly necessary to the gothic genre, just the feeling that something supernatural is happening – whether it is true or not. That feeling of dread is what the romance latches on, whether it is because of the seduction of power, or coercion, or protection from the mysterious forces that haunt the main character. In fact, most early gothics did not have any actual supernatural element at all.

I’ve always wondered why people think vampire books are inherently gothic. Thanks for this informative post, and I’ll be spreading it around for people to read!

This was a very interesting article, thank you. However, I do agree with Atrus: many of the early Gothic novels did not actually have supernatural elements. Ann Radcliffe is usually cited as the person who really codified the genre and in her novels the so-called supernatural elements turn out not to be supernatural at all.

As a literature student I was given a lecture precisely about origins of Gothic genre, in 18th and 19th Cry. As young literature student, I’ll only try only to reinterpret the points made here;

) which characterizes 18th Cry Gothic writing (not exclusively), after which we were given plot elements – torture, necromancy, necrophilia, sudden death, prophesies, demons and many other. All of them, at that time, used with a single purpose in mind – fascination through fear. In 18th Cry – Age of Sensation – the focus was laid upon extreme emotions/sensations, which were believed to enrich one’s understanding of life. Hero + heroine were also important – main hero was usually of a bad character, trying to take heroine by force; but very charismatic, powerful. She was just as educated and witty as him (!) and opposed him. All this was set in a medieval castle or other isolated place in wilderness, dungeons were also popular.

) which characterizes 18th Cry Gothic writing (not exclusively), after which we were given plot elements – torture, necromancy, necrophilia, sudden death, prophesies, demons and many other. All of them, at that time, used with a single purpose in mind – fascination through fear. In 18th Cry – Age of Sensation – the focus was laid upon extreme emotions/sensations, which were believed to enrich one’s understanding of life. Hero + heroine were also important – main hero was usually of a bad character, trying to take heroine by force; but very charismatic, powerful. She was just as educated and witty as him (!) and opposed him. All this was set in a medieval castle or other isolated place in wilderness, dungeons were also popular.

After lengthy introduction, we were given a nice graph – Freytag’s triangle (e.g.

With the progress into 19th Cry, further elements were added – passionate/destructive love affairs, mood of decay, disturbing/dramatic actions, extravagant writings. Therefore we can observe a shift from tranquility tinged with terror into sensational and horrible (where it pretty much ended today). In the 19th Cry this can be explained by the scientific progress (-> Frankenstien..) and disillusionment with society (-> Drakula). It was also at that time, when supernatural was introduced into Gothic with increasing popularity.

Please, don’t take this as a lecturing (it would be very poor anyway), but rather as a humble attempt to enhance the discussion with more .. uh, of ‘official’ doctrine, I suppose I could say, since it comes directly from University, backed up by lots of research..

All the credit goes to Uni of Huddersfield’s teachers, and in the (unlikely) case of extreme interest, I am happy to send anyone the whole presentation.